Copy Pasted From: http://bit.ly/g72Gd5 If you have a something awful account.

Petey posted:

Introduction

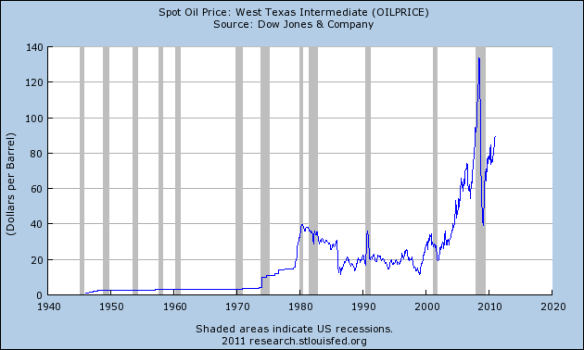

If you drive a car, carpool, or even occasionally go outside for a nice walk, you may have noticed that gas prices are through the roof right now. While oil is not quite as expensive as it was before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), it is getting close:

and certainly much higher than in recent months:

Why is this?

If you have not only been walking outside but occasionally flipping away from your anime television marathons to almost anything that even glances in the direction of news, you know that there is a bit of a hullabaloo in that warm and sandy part of the world where a lot of oil is from. You may have seen foreboding articles, likethis one from the BBC:

BBC posted:

Crude oil costs rise in Asia as Libyan unrest continues

Crude oil prices rose sharply during Asian trading hours on fears about the unrest in Libya…

Or Facebook posts from your goddamned idiot friends ironically “thanking” Libyans, Saudis, Egyptians, and everyone else browner than them for $4/gallon gas.

It is true that the unrest in the Middle East and North Africa has had some impact on gas prices. Though Libya produces only 1.5m gallons of oil a day (more context on this number to come), the demand for oil, as a key input of production, energy, transportation, and the entire global economy is relatively inelastic. That means that even very small shocks to the supply of oil can ripple quite quickly and drastically through the world.

But are there other explanations for this recent spike in gas prices other than brown people looking for freedom?

I’m so glad you asked.

Because the real reason for the recent spike in gas prices has, at best, an attenuated, ancillary, and secondary relationship to the current unrest in the Arab world.

The primary party is Wall Street.

The Commodities Bubble

In order to understand how Wall Street financiers are responsible for your pain at the pump, first we need to understand something about commodities trading.

Without needing to dig too deeply into Marx, it is for our purposes sufficient to define a commodity as something that can be bought and sold on a market, as they have been for thousands of years. You farm some wheat. You take it to market. You sell the wheat to someone else. You have traded a commodity.

Except that nowadays it doesn’t work precisely like that.

Trading Nothing At All: Examples from the Food Bubble

(why are we talking about food? It will make sense soon. Just read)

I highly recommend reading THe Food Bubble, an article in Harper’s Magazine. Some excerpts:

quote:

In 1991 nearly everything else that could be recast as a financial abstraction had already been considered. Food was pretty much all that was left. And so with accustomed care and precision, Goldman’s analysts went about transforming food into a concept. They selected eighteen commodifiable ingredients and contrived a financial elixir that included cattle, coffee, cocoa, corn, hogs, and a variety or two of wheat. They weighted the investment value of each element, blended and commingled the parts into sums, then reduced what had been a complicated collection of real things into a mathematical formula that could be expressed as a single manifestation, to be known thenceforward as the Goldman Sachs

Commodity Index. Then they began to offer shares.…

North America, the Saudi Arabia of cereal, sends nearly half its wheat production overseas, and an obscure syndicate known as the Minneapolis Grain Exchange remains the supreme price-setter for the continent’s most widely exported wheat, a high-protein variety called hard red spring. Other varieties of wheat make cake and cookies, but only hard red spring makes bread. Its price informs the cost of virtually every loaf on earth.

As far as most people who eat bread were concerned, the Minneapolis Grain Exchange had done a pretty good job: for more than a century the real price of wheat had steadily de- clined. Then, in 2005, that price began to rise, along with the prices of rice and corn and soy and oats and cooking oil. Hard red spring had long traded between $3 and $6 per sixty- pound bushel, but for three years Minneapolis wheat broke record after re- cord as its price doubled and then doubled again. No one was surprised when in the first quarter of 2008 trans- national wheat giant Cargill attributed its 86 percent jump in annual profits to commodity trading. And no one was surprised when packaged-food maker ConAgra sold its trading arm to a hedge fund for $2.8 billion. Nor when The Economist announced that the real price of food had reached its highest level since 1845, the year the magazine first calculated the number.

Nothing had changed about the wheat, but something had changed about the wheat market. Since Goldman’s innovation, hundreds of billions of new dollars had overwhelmed the actual supply of and actual demand for wheat, and rumors began to emerge that someone, somewhere, had cornered the market. Robber barons, gold bugs, and financiers of every stripe had long dreamed of controlling all of something everybody needed or de- sired, then holding back the supply as demand drove up prices. But there was plenty of real wheat, and American farmers were delivering it as fast as they always had, if not even a bit faster. It was as if the price itself had begun to generate its own demand—the more hard red spring cost, the more investors wanted to pay for it.

…

The global speculative frenzy sparked riots in more than thirty countries and drove the number of the world’s “food insecure” to more than a billion. In 2008, for the first time since such statistics have been kept, the proportion of the world’s population without enough to eat ratcheted upward.The ranks of the hungry had increased by 250 million in a single year, the most abysmal increase in all of human history.

…

enter several paragraphs of description of an ornate, cavernous building, where all bushels of physical wheat in the country were once traded, now completely empty

…

As a courtesy to the speculators who for decades had spent their workdays executing trades in the grain pits, the exchange had set up a new space a few stories above the old trading floor, a gray-carpeted room in which a few dozen beige cubicles were available to rent, some featuring a view of a parking lot. I had expected shouting, panic, confusion, and chaos, but no more than half the cubicles were occupied, and the room was silent. One of the grain traders was reading his email, another checking ESPN for the weekend scores, another playing soli- taire, another shopping on eBay for antique Japanese vases. “We’re trading wheat, but it’s wheat we’re never going to see,” Austin Damiani, a twenty-eight-year-old wheat broker, would tell me later that afternoon. “It’s a cerebral experience.”

…

After the combined credit crunch, real estate wreck, and stock-market meltdown now known as the Panic of 1857, U.S. grain merchants conceived a new stabilizing force: In return for a cash commitment today, farmers would sign a forward contract to deliver grain a few months down the line, on the expiration date of the contract. Since buyers could never be certain what the price of wheat would be on the date of delivery, the price of a future bushel of wheat was usually a few cents less than that of a present bushel of wheat. And while farmers had to accept less for future wheat than for real and present wheat, the guaranteed future sale protected them from plummeting prices and enabled them to use the promised payment as, say, collateral for a bank loan. These contracts let both producers and consumers hedge their risks, and in so doing reduced volatility.

The exchanges soon attracted a new species of merchant interested in numbers, not grain. This was the speculator. As the price of futures contracts fluctuated in daily trading, the speculator sought to cash in through strategic buying and selling. And since the speculator had neither real wheat to sell nor a place to store any he might purchase, for every “long” position he took (a promise to buy future wheat), he would eventually need to place an equal and opposite “short” position (a promise to sell). Farmers and millers welcomed the speculator to their market, for his perpetual stream of buy and sell orders gave them the freedom to sell and buy their actual wheat just as they pleased.

Under the new system, farmers and millers could hedge, speculators could speculate, the market remained liquid, and yet the speculative futures price could never move too far from the “spot” (or actual) price: every ten weeks or so, when the delivery date of the contract approached, the two prices would converge, as everyone who had not cleared his position with an equal and opposite position would be obligated to do just that. The virtuality of wheat futures would settle up with the reality of cash wheat, and then, as the contract ex- pired, the price of an ideal bushel would be “discovered” by hedger and speculator alike.…

And despite the occasional market collapse (onions in 1957, Maine potatoes in 1976), for more than a century the basic strategy and tactics of futures trading remained the same, the price of wheat remained stable, and increasing numbers of people had plenty to eat.

The decline of volatility, good news for the rest of us, drove bankers up the wall. Clearly, some innovation was in order. In the midst of this dead mar- ket, Goldman Sachs envisioned a new form of commodities invest- ment, a product for investors who had no taste for the complexities of corn or soy or wheat, no interest in weather and weevils, and no desire for getting into and out of shorts and longs—investors who wanted nothing more than to park a great deal of money somewhere, then sit back and watch that pile grow. The managers of this new product would acquire and hold long positions, and nothing but long positions, on a range of commodities futures. They would not hedge their futures with the actual sale or purchase of real wheat (like a bona-fide hedger), nor would they cover their positions by buying low and selling high (in the grand old fashion of commodities speculators). In fact, the structure of commodity index funds ran counter to our nor- mal understanding of economic theo- ry, requiring that index-fund manag- ers not buy low and sell high but buy at any price and keep buying at any price. No matter what lofty highs long wheat futures might attain, the managers would transfer their long positions into the next long futures contract, due to expire a few months later, and repeat the roll when that contract, in turn, was about to expire— thus accumulating an everlasting, ever-growing long position, unremittingly regenerated.

“You’ve got to be out of your freak- ing mind to be long only,” Rothbart said. “Commodities are the riskiest things in the world.”

But Goldman had its own way to offset the risks of commodities trading—if not for their clients, then at least for themselves. The strategy, standard practice for most index funds, relied on “replication,” which meant that for every dollar a client invested in the index fund, Goldman would buy a dollar’s worth of the un- derlying commodities futures (minus management fees). Of course, in or- der to purchase commodities futures,the bankers had only to make a “good-faith deposit” of something like 5 percent. Which meant that they could stash the other 95 percent of their investors’ money in a pool of Treasury bills, or some other equally innocuous financial cranny, which they could subsequently leverage into ever greater amounts of capital to utilize to their own ends, whatever they might be. If the price of wheat went up, Goldman made money. And if the price of wheat fell, Gold- man still made money—not only from management fees, but from the profits the bank pulled down by in- vesting 95 percent of its clients’ mon- ey in less risky ventures. Goldman even made money from the roll into each new long contract, every in- stance of which required clients to pay a new set of transaction costs.

The bankers had figured out how to extract profit from the commodities market without taking on any of the risks they themselves had introduced by flooding that same market with long orders. Unlike the wheat producers and the wheat speculators, or even Goldman’s own customers, Goldman had no vested interest in a stable commodities market. As one index trader told me, “Commodity funds have historically made money—and kept most of it for themselves.”…

Government regulators, far from preventing this strange new way of accumulating futures, actively en- couraged it. Congress had in 1936 created a commission that curbed “excessive speculation” by limiting large holdings of futures contracts to bona-fide hedgers. Years later, the modern-day Commodity Futures Trading Commission continued to set absolute limits on the amount of wheat-futures contracts that could be held by speculators. In 1991, that limit was 5,000 contracts. But after the invention of the commodity index fund, bankers convinced the commission that they, too, were bona-fide hedgers. As a result, the commission issued a position-limit exemption to six commodity index traders, and within a decade those funds would be permitted to hold as many as 130,000 wheat-futures contracts at any one time.

…

As long as the commodities brokers kept rolling over their futures, it looked as though the day of reckoning might never come. If no one contemplated the effects that this accumulation of long-only futures would eventually have on grain markets, perhaps it was because no one had never seen such a massive pile of long-only futures.

From one perspective, a complicated chain of cause and effect had inflated the food bubble. But there were those who understood what was happening to the wheat markets in simpler terms. “I don’t have to pay anybody for anything, basi- cally,” one long-only indexer told M me. “That’s the beauty of it.”

…

The wheat harvest of 2008 turned out to be the most bountiful the world had ever seen, so plentiful that even as hundreds of millions slowly starved, 200 million bushels were sold for animal feed. Livestock owners could afford the wheat; poor people could not. Rather belatedly, real wheat had shown up again—and lots of it. U.S. Department of Agri- culture statistics eventually revealed that 657 million bushels of 2008 wheat remained in U.S. silos after the buying season, a record-breaking “carryover.”

…

About two thirds of the Goldman index remains devoted to crude oil, gasoline, heating oil, natural gas, and other energy- based commodities.Wheat was noth- ing but an indexical afterthought, accounting for less than 6.5 percent of Goldman’s fund.

And then it occurred to me: It was neither an individual nor a corpora- tion that had cornered the wheat market. The index funds may never have held a single bushel of wheat, but they were hoarding staggering quantities of wheat futures, billions of promises to buy, not one of them ever to be fulfilled. The dreaded market corner had emerged not from a shortage in the wheat supply but from a much rarer economic occurrence, a shock inspired by the ceaseless call of index funds for wheat that did not exist and would never need to exist: a demand shock.

The Oil Bubble

The fundamental dynamic at hand in the wheat bubble was (and is) present in the oil bubble. The Arab uprisings are a convenient scapegoat at the moment, but no such issues existed in the runup to the GFC, when oil prices were even higher than they are now.

Instead, as with wheat, the issue was primarily one of Wall Street. I quote here from Chapter 4 of Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia, an absolute must-read for anyone interested in learning why the GFC occured and what skullfuckery Wall Street remains engaged in. There is some overlap with the Harper’s article, but it is worth it.

Quoth Taibbi:

quote:

McCain, amazingly, spent all summer telling us reporters that the reason for the spike in gas prices was that socialists like Barack Obama were refusing to permit immediate drilling for oil off the coast of Florida…How about Barack Obama? He offered a lot of explanations, too. In many ways the McCain-Obama split on the gas prices issue was a perfect illustration of how left-right politics works in this country. McCain blamed the problem, both directly and indirectly, on a combination of government, environmentalists, and foreigners.

Obama knew his audience and aimed elsewhere. He blamed the problem on greedy oil companies and also blamed ordinary Americans for their wastefulness, for driving SUVs and other gas-guzzlers.Both candidates were selling the public a storyline that had nothing to do with the truth. Gas prices were going up for reasons completely unconnected to the causes these candidates were talking about. What really happened was that Wall Street had opened a new table in its casino. The new gaming table was called commodity index investing. And when it became the hottest new

game in town, America suddenly got a very painful lesson in the glorious possibilities of taxation without representation. Wall Street turned gas prices into a gaming table, and when they hit a hot streak we ended up making exorbitant involuntary payments for a commodity that one simply cannot live without…

All the way back in 1936, after gamblers disguised as Wall Street brokers destroyed the American economy, the government of Franklin D. Roosevelt passed a law called the Commodity Exchange Act that was specifically designed to prevent speculators from screwing around with the prices of day-to-day life necessities like wheat and corn and soybeans and oil and gas.

Let’s say you’re that cereal company and your business plan for the next year depends on your being able to buy corn at a maximum of $3.00 a bushel. And maybe corn right now is selling at $2.90 a bushel, but you want to insulate yourself against the risk that prices might skyrocket in the next year. So you buy a bunch of futures contracts for corn that give you the right—say, six months from now, or a year from now—to buy corn at $3.00 a bushel.

Now, if corn prices go up, if there’s a terrible drought and corn becomes scarce and ridiculously expensive, you could give a damn, because you can buy at $3.00 no matter what. That’s the proper use of the commodities futures market.It works in reverse, too—maybe you grow corn, and maybe you’re worried about a glut the following year that might, say, drive the price of corn down to $2.50 or below. So you sell futures for a year from now at $2.90 or $3.00, locking in your sale price for the next year. If that drought happens and the price of corn skyrockets, you might lose out, but at least you can plan for the future based on a reasonable price.

These buyers and sellers of real stuff are the physical hedgers. The FDR administration recognized, however, that in order for the market to properly function, there needed to exist another kind of player—the speculator. The entire purpose of the speculator, as originally envisioned by the people who designed this market, was to guarantee that the physical hedgers, the real

players, could always have a place to buy and/or sell their products.

Again, imagine you’re that corn grower but you bring your crop to market at a moment when the cereal company isn’t buying. That’s where the speculator comes in. He buys up your corn and hangs on to it. Maybe a little later, that cereal company comes to the market looking for corn—but there are no corn growers selling anything at that moment. Without the speculator there, both grower and cereal company would be fucked in the instance of a temporary disruption.

With the speculator, however, everything runs smoothly. The corn grower goes to the market with his corn, maybe there are no cereal companies buying, but the speculator takes his crop at $2.80 a bushel. Ten weeks later, the cereal guy needs corn, but no growers are there—so he buys from the speculator, at $3.00 a bushel. The speculator makes money, the grower unloads his crop, the cereal company gets its commodities at a decent price, everyone’s happy.This system functioned more or less perfectly for about fifty years. It was tightly regulated by the government, which recognized that the influence of speculators had to be watched carefully. If speculators were allowed to buy up the whole corn crop, or even a big percentage of it, for instance, they could easily manipulate the price. So the government set up position limits, which guaranteed that at any given moment, the trading on the commodities markets would be dominated by the physical hedgers, with the speculators playing a purely functional role in the margins to keep things running smoothly.

…

in 1991, J. Aron—the Goldman subsidiary—wrote to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (the government agency overseeing this market) and asked for one measly exception to the rules.

The whole definition of physical hedgers was needlessly restrictive, J. Aron argued. Sure, a corn farmer who bought futures contracts to hedge the risk of a glut in corn prices had a legitimate reason to be hedging his bets. After all, being a farmer was risky! Anything could happen to a farmer, what with nature being involved and all!

Everyone who grew any kind of crop was taking a risk, and it was only right and natural that the government should allow these good people to buy futures contracts to offset that risk.

But what about people on Wall Street? Were not they, too, like farmers, in the sense that they were taking a risk, exposing themselves to the whims of economic nature? After all, a speculator who bought up corn also had risk—investment risk. So, Goldman’s subsidiary argued, why not allow the poor speculator to escape those cruel position limits and be allowed to make transactions in unlimited amounts? Why even call him a speculator at all? Couldn’t J. Aron call itself a physical hedger too? After all, it was taking real risk—just like a farmer!

On October 18, 1991, the CFTC-in the person of Laurie Ferber, an appointee of the first President Bush—agreed with J. Aron’s letter. Ferber wrote that she understood that Aron was asking that its speculative activity be recognized as “bona fide hedging”—and, after a lot of jargon and legalese, she accepted that argument. This was the beginning of the end for position limits and for the proper balance between physical hedgers and speculators in the energy markets.

In the years that followed, the CFTC would quietly issue sixteen similar letters to other companies. Now speculators were free to take over the commodities market. By 2008, fully 80 percent of the activity on the commodity exchanges was speculative, according to one congressional staffer who studied the numbers—”and that’s being conservative,” he said.…

One congressional staffer, a former aide to the Energy and Commerce Committee, just happened to be there when certain CFTC officials mentioned the letters offhand in a hearing. “I had been invited by the Agriculture Committee to a hearing the CFTC was holding on energy,” the aide recounts. “And suddenly in the middle of it they start saying, ‘Yeah, we’ve been issuing these letters for years now.’ And I raised my hand and said, ‘Really? You issued a letter? Can I see it?’ And they were like, ‘Uh-oh.’

“So we had a lot of phone conversations with them, and we went back and forth,” he continues. “And finally they said, ‘We have to clear it with Goldman Sachs.’ And I’m like, ‘What do you mean, you have to clear it with Goldman Sachs?'”

…

[What you’re doing when you invest in the S&P GSCI is buying monthly futures contracts for each of these commodities. If you decide to simply put a thousand dollars into the S&P GSCI and leave it there, the same way you might with a mutual fund, this is a little more complicated—what you’re really doing is buying twenty-four different monthly futures contracts, and then at the end of each month you’re selling the expiring contracts and buying a new set of twenty-four contracts. After all, if you didn’t sell those futures contracts, someone would actually be delivering barrels of oil to your doorstep. Since you don’t really need oil, and you’re just investing to make money, you have to continually sell your futures contracts and buy new ones in what amounts to a ridiculously overcomplex way of betting on the prices of oil and gas and cocoa and coffee.

This process of selling this month’s futures and buying the next month’s futures is called rolling. Unlike shares of stock, which you can simply buy and hold, investing in commodities involves gazillions of these little transactions made over time. So you can’t really do it by yourself: you usually have to outsource all of this activity, typically to an investment bank, which makes fees handling this process every month.

…

To look at this another way—just to make it easy—let’s create something we call the McDonaldland Menu Index (MMI). The MMI is based upon the price of eleven McDonald’s products, including the Big Mac, the Quarter Pounder, the shake, fries, and hash browns. Let’s say the total price of those eleven products on November l, 2010, is $37.90. Now let’s say you bet $1,000 on the McDonaldland Menu Index on that date, November 1. A month later, the total price of those eleven products is now $39.72.

Well, gosh, that’s a 4.8 percent price increase. Since you put $1,000 into the MMI on November 1, on December 1 you’ve now got $1,048. A smart investment!

Just to be clear—you didn’t actually buy $1,000 worth of Big Macs and fries and shakes. All you did is bet $1,000 on the prices of Big Macs and fries and shakes.But here’s the thing: if you were just some schmuck on the street and you wanted to gamble on this nonsense, you couldn’t do it, because your behavior would be speculative and restricted under that old 1936 Commodity Exchange Act, which supposedly maintained that delicate balance between speculator and physical hedger (i.e., the real producers/consumers). Same goes for a giant pension fund or a trust that didn’t have one of those magic letters. Even if you wanted into this craziness, you couldn’t get in, because it was barred to the Common Speculator. The only way for you to get to the gaming table was, in essence, to rent the speculator-hedger exemption that the government had quietly given to companies like Goldman Sachs via those sixteen letters.

…

[T]he people who managed the great pools of money in this world—the pension funds, the funds belonging to trade unions, and the sovereign wealth funds, those utterly gigantic quasi-private pools of money run by foreign potentates, usually Middle Eastern states looking to do something with their oil profits. It meant someone was offering them a new place to put their money. A safe place. A profitable place.

Why not bet on something that people can’t do without—like food or gas or oil? What could be safer than that? As if people will ever stop buying gasoline! Or wheat! Hell, this is America. Motherfuckers be eating pasta and cran muffins by the metric ton for the next ten centuries! Look at the asses on people in this country. Just let them try to cut back on wheat, and sugar, and corn!

But there were several major problems with this kind of thinking—i.e., the notion that the prices of oil and gas and wheat and soybeans were something worth investing in for the long term, the same way one might invest in stock.

For one thing, the whole concept of taking money from pension funds and dumping it long-term into the commodities market went completely against the spirit of the delicate physical hedger/speculator balance as envisioned by the 1936 law. The speculator was there, remember, to serve traders on both sides. He was supposed to buy corn from the grower when the cereal company wasn’t buying that day and sell corn to the cereal company when the farmer lost his crop to bugs or drought or whatever. In market language, he was supposed to “provide liquidity.”

The one thing he was not supposed to do was buy buttloads of corn and sit on it for twenty years at a time. This is not “providing liquidity.” This is actually the opposite of that. It’s hoarding.…

The other problem with index investing is that it’s “long only.” In the stock market, there are people betting both for and against stocks. But in commodities, nobody invests in prices going down. “Index speculators lean only in one direction-long—and they lean with all their might,” says Masters. Meaning they push prices only in one direction: up.

The other problem with index investing is that it brings tons of money into a market where people traditionally are extremely sensitive to the prices of individual goods. When you have ten cocoa growers and ten chocolate companies buying and selling back and forth a total of half a million dollars on the commodities markets, you’re going to get a pretty accurate price for cocoa. But if you add to the money put in by those twenty real traders $10 million from index speculators, it queers the whole deal. Because the speculators don’t really give a shit what the price is. They just want to buy $10 million worth of cocoa contracts and wait to see if the price goes up.

To use an example frequently offered by Masters, imagine if someone continually showed up at car dealerships and asked to buy $500,000 worth of cars. This mystery person doesn’t care how many cars, mind you, he just wants a half million bucks’ worth. Eventually, someone is going to sell that guy one car for $500,000. Put enough of those people out there visiting car dealerships, your car market is going to get very weird very quickly. Soon enough, the people who are coming into the dealership looking to buy cars they actually plan on driving are going to find that they’ve been priced out of the market.

An interesting side note to all of this: if you think about it logically, there are few reasons why anyone would want to invest in a rise in commodity prices over time. With better technology, the cost of harvesting and transporting commodities like wheat and corn is probably going to go down over time, or at the very least is going to hover near inflation, or below it. There are not many good reasons why prices in valued commodities would rise—and certainly very few reasons to expect that the prices of twenty-four different commodities would all rise over and above the rate of inflation over a certain period of time.

What all this means is that when money from index speculators pours into the commodities markets, it makes prices go up. In the stock markets, where again there is betting both for and against stocks (long and short betting), this would probably be a good thing. But in commodities, where almost all speculative money is betting long, betting on prices to go up, this is not a good thing—unless you’re one of the speculators.

Anyway, from 2003 to July 2008, the amount of money invested in commodity indices rose from $13 billion to $317 billion—a factor of twenty-five in a space of a little less than five years.

By an amazing coincidence, the prices of all twenty-five commodities listed on the S&P GSCI and the Dow-AIG indices rose sharply during that time. Not some of them, not all of them on the aggregate, but all of them individually and in total as well.

The average price increase was 200 percent. Not one of these commodities saw a price decrease. What an extraordinarily lucky time for investors!And the top oil analyst at Goldman Sachs quietly conceded, in May 2008, that “without question the increased fund flow into commodities has boosted prices.”

One thing we know for sure is that the price increases had nothing to do with supply or demand. In fact, oil supply was at an all-time high, and demand was actually falling. In April 2008 the secretary-general of OPEC, a Libyan named Abdalla El-Badri, said flatly that “oil supply to the market is enough and high oil prices are not due to a shortage of crude.” The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) agreed: its data showed that worldwide oil supply rose from 85.3 million barrels a day to 85.6 million from the first quarter to the second that year, and that world oil demand dropped from 86.4 million barrels a day to 85.2 million.Not only that, but people in the business who understood these things knew that the supply of oil worldwide was about to increase. Two new oil fields in Saudi Arabia and another in Brazil were about to start dumping hundreds of thousands more barrels of oil per day into the market. Fadel Gheit, an analyst for Oppenheimer who has testified before Congress on the issue, says that he spoke personally with the secretary-general of OPEC back in 2005, who insisted that oil prices had to be higher for a very simple reason—increased security costs.

“He said to me, if you think that all these disruptions in Iraq and in the region… look, we haven’t had a single tanker attacked, and there are hundreds of them sailing out every day. That costs money, he said. A lot of money.”

So therefore, Gheit says, OPEC felt justified in raising the price of oil. To 45 dollars a barrell At the height of the commodities boom, oil was trading for three times that amount.“I mean, oil shouldn’t have been at sixty dollars, let alone a hundred and forty-nine,” Gheit says.

This was why there were no lines at the gas stations, no visible evidence of shortages. Despite what we were being told by both Barack Obama and John McCain, there was no actual lack of gasoline. There was nothing wrong with the oil supply.

All of these factors contributed to what would become a historic spike in gas prices in the summer of 2008. The press, when it bothered to cover the story at all, invariably attributed it to a smorgasbord of normal economic factors. The two most common culprits cited were the shaky dollar (investors nervous about keeping their holdings in U.S. dollars were, according to some, more likely to want to shift their holdings into commodities) and the increased worldwide demand for oil caused by the booming Chinese economy.

Both of these factors were real. But neither was any more significant than the massive inflow of speculative cash into the market.

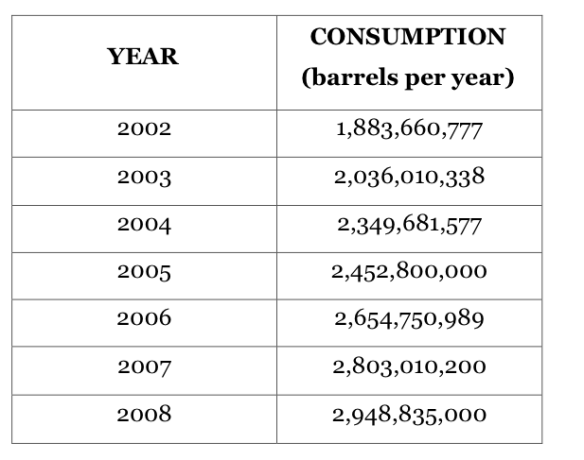

The U.S. Department of Energy’s own statistics prove this to be the case. It was true, yes, that China was consuming more and more oil every year. The statistics show the Chinese appetite for oil did in fact increase over time:

If you add up the total increase between each of those years, i.e., the total increase in Chinese oil consumption over the five and a half years between the start of 2003 and the middle of 2008, it turns out to be just under a billion Barrels — 992,261,824 to be exact.During the same time period, however, the increase in index speculator cash pouring into the commodities markets for petroleum products was almost exactly the same—speculators bought 918,966,932 barrels, according to the CFTC.

Oil shot up like a rocket, hitting an incredible high of $149 a barrel in July 2008, taking with it prices of all the other commodities on the various indices. Food prices soared along with energy prices. According to some estimates by international relief agencies—estimates that did not blame commodity speculation for the problem, incidentally—some 100 million people joined the ranks of the hungry that summer worldwide, because of rising food prices.

Then it all went bust, as it had to, eventually. The bubble burst and oil prices plummeted along with the prices of other commodities. By December, oil was trading at $33.

And then the process started all over again.

And Today

So, to briefly recap what we’ve learned thus far:

– buyers and sellers trade commodities on markets

– speculators help provide liquidity, by buying when sellers wish to sell but no

one wishes to buy, and selling when buyers wish to buy but no one wishes to sell

– however, the biggest banks got exemptions from the government to purchase huge positions on commodities

– instead of selling these positions to buyers, these banks hang on to them, because their investors are all “long”, meaning they think the price is going to go up; at the end of every month, they just “roll over” their positions, and keep on holding the things they were supposed to have sold

– because none of the banks sell what they hold, the price goes up; because the price goes up, more people make money on their positions; because they make more money on their positions they buy more stuff and don’t sell what they hold; and on and on forever

Are we seeing evidence of this today?

Yes.

Remember how Libya is being blamed for diminishing the world’s oil supply with its 1.5 million barrels per day of output?

Well, the investment bank JP Morgan owns over 270 million barrels of oil – equivalent to almost a third of the United States National Emergency Reserve – so much so, in fact, that they, and other banks, are now buying supertankers to store their excess reserves offshore because they’ve simply run out of space on land.

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?…id=aZtS4TC9mxJM

quote:

June 3 (Bloomberg) — JPMorgan Chase & Co., the second- largest U.S. bank by deposits, hired a newly built supertanker to store heating oil off Malta, shipbrokers reported, in the company’s first such booking in at least five years.

JPMorgan, which has never hired an oil tanker based on data compiled by Bloomberg going back five years, follows companies including Citigroup Inc.’s Phibro LLC unit and BP Plc in hiring ships to store crude or oil products at sea. The firms are seeking to take advantage of higher prices later in the year.

JPMorgan hired the ship at $35,000 to $41,000 a day, according to the broker reports. The bank is also paying $1.6 million for the ship to sail from Singapore to Europe without a cargo, the brokers said. Long Range 2 tankers cost about $25,000 a day for storage, according to Riverlake Shipping.

Traders were already using smaller tankers to store record volumes of jet fuel and heating oil in Europe as on-shore tanks filled up, D/S Torm A/S, Europe’s biggest oil products shipping line, said April 3.

In Conclusion

The current spike in gas prices is not primarily a result of anything to do with the freedom fighters in the Arab world. Nor is it a result of OPEC’s production levels, which would suggest a far lower $/gallon than can be found on the open market.

Rather, the spikes are primarily a result of the speculative market on oil. This speculative market is driven by the practices of the biggest banks, who have special exemptions to treat commodities like a casino, who have zero incentive to appropriately hedge their bets, who do not provide the liquidity they were designed to provide, and who generally provide nothing of value to society except to push prices of things higher and higher so that very rich people will continue to invest with them.

I hope you have all learned something from this thread, and I hope you will agree with me that the next time you gasp softly at the price of bread in the supermarket, or read about flour shortages and starvation in Mexico, or have trouble making ends meet because can barely afford to even drive to your job, your first response, and heartfelt response, will be forevermore:

wow, this was an incredibly depressing read. makes you feel unbelievably helpless. i’m looking at my credit card bill and 70% of it is for gas. 70%!